I have said several times in different articles that contributing to the Linux kernel is both satisfying and rewarding.

Some people have asked me if by rewarding I mean that you get some kind of public recognition from the community, maybe some sort of digital award you can add to your resume. Today I saw that some of my bug fixes were applied to some of the latest 6.10 release candidates, and apparently I won’t have to wait for the next merge window to reach the 100-patch mark in the mainline Linux kernel. Now I can tell you what happens when you get that far.

If you just sent your first patches, but nothing special happened, keep on working hard, and the awards will come…

Would you like to know what happens when you get 100 patches applied to the mainline Linux kernel? Alright, I am going to tell you a secret: you receive a certificate for your unrivalled achievement from the Linux Foundation with a dedication by Linus Torvalds!

Look at mine:

Jokes aside, I believe that tracking the status of your patchsets as well as your overall progression is not a bad idea as long as you don’t get obsessed with it. In this article I would like to summarize what I have done so far, show some simple mechanisms to follow your contributions, and my opinion about the value of having X patches applied to the Linux kernel.

Content:

- Following the status of your contributions

- Simple metrics: what do my contributions look like?

- Quantity vs Quality: hard to measure

- My opinion about such metrics

1. Following the status of your contributions

That is something you should aim for. Sending series and forgetting about them 10 minutes later is not a great idea because receiving feedback is highly probable, but by no means guaranteed. Not only because your series could be ignored for a number of reasons, but also because it could have been applied without you being told. That does not happen often, but a few of my patches went that way. Spam filters and other issues related to the email provider are also a real thing. Therefore, I would recommend you to check the status of your work upstream from time to time.

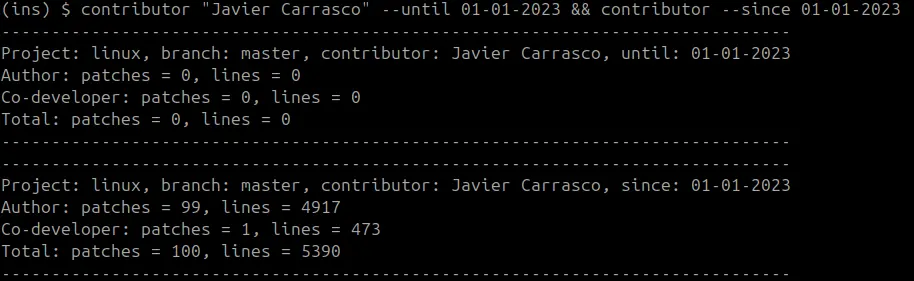

Apart from receiving direct feedback from reviewers and maintainers via email, there are several ways to track the status of your contributions. The most basic, yet reliable one, is git log. You just have to check out the branch where you would expect your commits to be (e.g. master branch of mainline, linux-next, or a subsystem tree), and run git log --author="your_name or email with any extra options you might require. Of course, you can write your own scripts based on git log to make it more powerful and tailored to your needs: number of commits since a given version, number of fixes, etc.

If you do so, you will probably see sporadically how many commits you have in the kernel tree. In my case I have written my own scripts to follow the progression of my mentees from the Linux Kernel Mentorship Program (LKMP) (of course I know what you are breaking apart, even when you “forget” to CC me ![]() ), and I can use them to track mine as well.

), and I can use them to track mine as well.

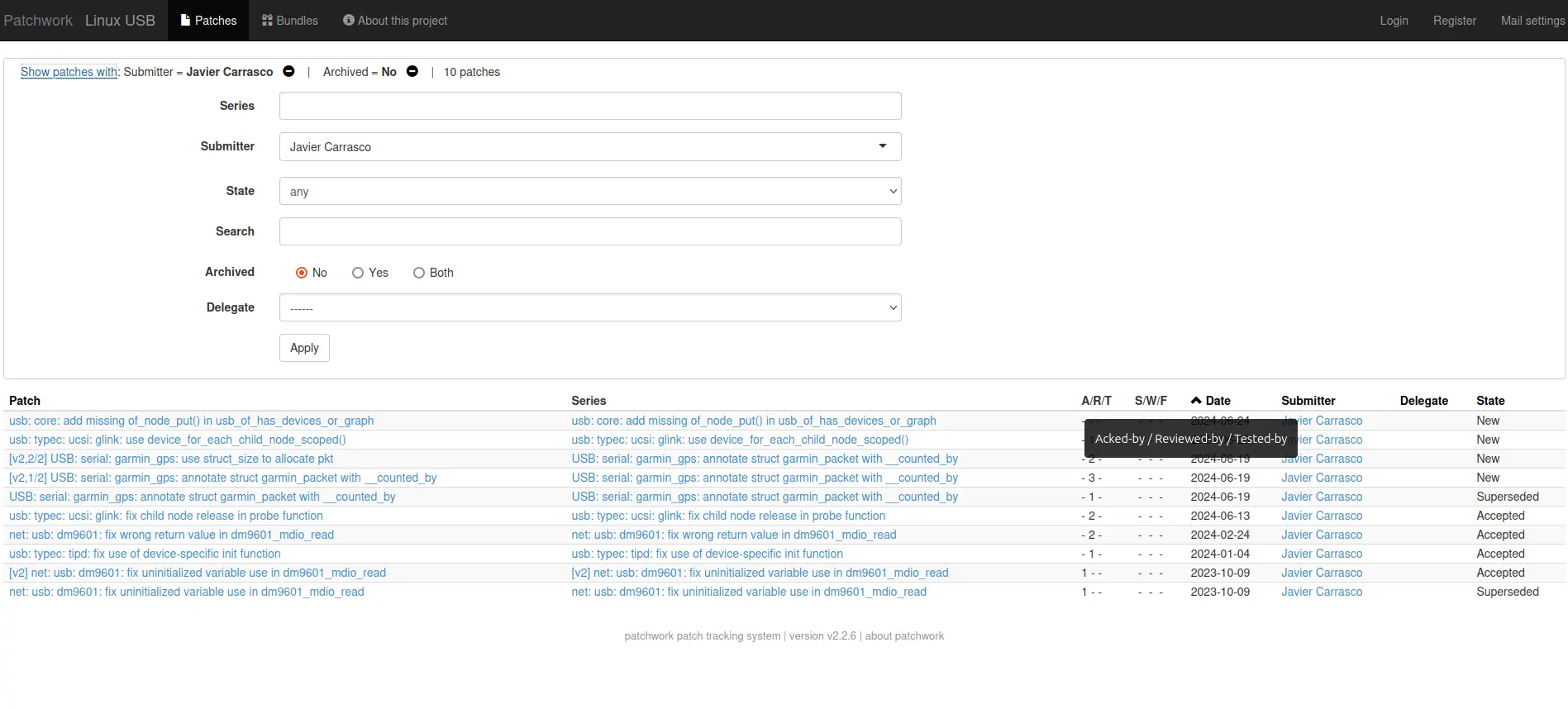

There are some other options out there like subsystem patchworks. Many subsystems use patchwork to keep a list of all patches sent to their mailing lists, and it is sometimes the fastest approach to see the status of all patchsets, including yours: you can see their general state (New, Superseded, Accepted…), filter them, or check what tags they got.

I must say that some subsystems simply ignore their patchwork (the tags like Reviewed-by are automatically tracked, though), and the tool itself is not perfect. For example, I have contributed to USB with two accounts, but I could only get the list for one of them. If you know a trick to list multiple authors, please let me know and I will update this point.

Another tool you probably know already is lore.kernel.org, a mailing list archive and interface for all Linux kernel discussions. Among many other things, you can track your submissions and all the replies you received. In principle, you should have received them as a reply to your email, but if for whatever reason you didn’t, it will be on lore.kernel.org for sure. And if you already access lore.kernel.org on a regular basis, lei (officially available for multiple distros) is a nice interface that will automate some steps you might have been repeating over and over again.

Now, let’s see an example about what metrics someone can get quickly and without much effort to get some rough idea about what has been done and accepted so far. I will also discuss the differences between contributing as a hobbyist and as a “professional”.

2. Simple metrics: what do my contributions look like?

I have two email addresses that I use to send patches: a personal one for my contributions as a hobbyist, and the company email address for my contributions as a “professional”. 75% of my contributions were made as a hobbyist, and when I look at linux-next, this proportion will not change much within the next weeks. How come only 25% of my contributions were made at work? Simply because as an embedded systems engineer, I have several tasks apart from Linux kernel development such as bringing up SoC-based boards, and BSP development.

Anyway, the difference between the patches coming from work and the homemade ones is noticeable. The first group is more focused on adding hardware support for some specific functionality we need for our systems, and it is basically limited to 3-4 subsystems. The second one is rather random: a bunch of bug fixes, a couple of new drivers for sensors I use in personal projects, and cleanups while learning new stuff (often spin-offs from my articles) in 8-10 subsystems. I do that for fun and to learn, so I don’t stick to any specific area.

How many patches belong to each category I mentioned? I took a quick look at the git logs, and it’s more or less as follows:

- Bug fixes: 20% -> if your fixes start with “fix…” or use the “Fixes:” tag (they should), they are easy to find.

- New drivers/devices: 10% -> you usually know what drivers you authored, also easy to track.

- New features: 30% -> less obvious to find on a list, but mine is still not that huge.

- Cleanups: 40% -> basically the rest.

Those numbers are tricky, though: most of the cleanup patches only modify a couple of lines of code (dt-binding conversions aside), while new drivers add several hundreds. New features (e.g. extending a driver to support some functionality the hardware offers) usually require something between 20 and 100 lines, and bug fixes are often single-liners. Is the removal of an explicit void * cast, making a struct const, or adding a missing .gitignore exactly the same amount of work as adding a new driver? Obviously not.

Should we then count the number of modified lines instead? That takes me to the next section.

3. Quantity vs Quality: hard to measure

Apparently, I have added/modified/deleted around 5400 lines of code, which results in ~54 lines/patch. Is that much? Well, ask someone who only submits fully-functional device drivers, and everything under 250 lines/patch will be peanuts. Ask “professional” bug fixers (they do exist), and they will probably say that they seldom need to modify more than 5-10 lines per patch.

If we follow a “the more lines, the better” reasoning, someone could ask if an easy dt-binding conversion (a few dozens of lines, often straightforward) is much more valuable than fixing a bug in a single line of code. Personally, I value the bug fix more because it usually implies deep understating of the code to identify the issue and find the right fix as well as knowing debugging tools and methodologies.

What matters then? As usual, the answer is it depends. Raw numbers don’t say much, but we are developers and even if we never wrote code for the Linux kernel, we all have a feeling about what a low-impact patch is, and what a high-impact patch could mean. Although that sounds rather subjective, and in many cases it is, some cases are clear: deleting 50 unused variables is something the compiler will (in principle) do anyway, and dropping average power consumption in arm64 by 10% sounds like an amazing achievement.

Having sent many patches or having modified many lines of code has some value by itself because it means that at least you know the workflow and the tools required to contribute to the Linux kernel, and you are probably familiar with some subsystem(s). Nevertheless, nothing beats our own judgment based on the code itself. Code neither lies nor pretends!

4. My opinion about such metrics

If you are a consultant or your company can profit from such advertising, paying attention to the number of patches/lines added to the Linux kernel is a good idea. Actually, most of the service providers that work on OSS use their contributions to advertise themselves, and they even publish reports with their weekly/monthly/annual contributions. You have probably seen such reports on LinkedIn or at the beginning of their talks in OSS conferences.

That makes perfect sense, and it’s even good for the community because they have to contribute to stay visible and keep reputation. No wonder why some low-impact cleanup series with 40+ patches (add const, drop unused, etc.) come from those companies. They have to deliver high-impact code too (which they do, and a lot), but showing up at the top-end of the lists is not to be neglected either. There is even this Kernel Patch Statistic, where patches and modified lines are listed by author, but also by company. Once again, competition is always welcome.

I remember a podcast where Greg K-H talked about that site, mentioning that someone had to do the low-impact cleanup, which in the end generates many patches for companies and individuals to climb they way up the list ![]()

What about the rest of kernel hackers? I can speak for myself. First I had to reach 5-10 patches to graduate from the LKMP, so I counted every single contribution. Since then, the numbers don’t matter much to me, because as I said, I believe impact is key. At the beginning it was a good way to check if I was progressing or not, and the first marks (1, 5, 10, 20) really worked as motivators.

But once you reach a higher pace and start sending patches to several subsystems, you forget about that without noticing. Getting a new patch applied is always good news, but when you are working on multiple, unrelated series at the same time, you just move on and go for the next one.

On the other hand, I would never criticize someone who counts every patch and wants to reach X patches by the end of the year or whatever. If that helps to get a better kernel, thanks a lot for your work and don’t let anyone tell you what should matter to you!

That’s all for today. Reviewing my contributions so far was interesting for me to see what I have been doing lately. It is not that long that I sent my first patch, and I am happy about my learning curve and the variety of my patches. But this analysis was enough for good; time to hack again!

Enjoy and share knowledge!