One of the most common criticisms of the C programming language is that dynamically allocated objects are not automatically released. And those who say this are right: memory leaks are a very common issue in C code, including the Linux kernel. Does that mean that C is useless, and the whole kernel should be rewritten in Rust as soon as possible? Definitely not, and even though some code is being rewritten in Rust, the great majority of the new code added with every release is still in C, and that will not change any soon. Instead, we should try to mitigate current pitfalls with new solutions… or simply start using the existing ones, like the Linux kernel recently did.

Content:

- Background: underutilized cleanup compiler attribute

- Walkthrough: the __free() macro step by step

- Return valid memory, but keep on using auto cleanup!

- Initialize your variables, and fear any “goto”

- Why Rust then?

- Why 1/2?

1. Background: underutilized cleanup compiler attribute

Note: this section paraphrases/plagiarizes/summarizes some code from include/linux/cleanup.h as well as this article by Jonathan Corbet on LWN.net, which I strongly recommend. Here I will just digest the key points and add some code snippets for complete noobs ![]()

Both GCC and Clang support a variable attribute called cleanup, which adds a “callback” that runs when the variable goes out of scope. If you never used compiler attributes, it is as simple as placing __attribute__ with the required attribute inside brackets right after the variable declaration. The cleanup attribute expects a function that takes a pointer to the variable type:

void cleanup_function(int *foo) {}

int foo __attibute (__cleanup__(cleanup_fuction));

Whenever foo goes out of scope, cleanup_function will be called. Here is a very simple example you can try and tweak:

/* cleanup.c */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void cleanup_function(int *foo)

{

printf("foo: I do! The answer is %d.\n", *foo);

}

int main()

{

int foo __attribute ((__cleanup__(cleanup_function))) = 42;

printf("What's the answer to everything?\n");

printf("main: I don't know, bye!\n");

return 0;

}

Let’s compile and run:

gcc -o cleanup cleanup.c

./cleanup

What's the answer to everything?

main: I don't know, bye!

foo: I do! The answer is 42.

If you can print a message, you can do more interesting stuff like freeing allocated memory, unlocking mutexes, and so on. I bet you are starting to grasp what we are aiming to achieve with this attribute.

Is that new magic? Well, the cleanup attribute exists in GCC since v3.3, which was released in 2003! Ok, then we have been using it in the Linux kernel for decades, right? Not really. It was first introduced in 2023 by Peter Zijlstra. Why? I don’t know. Maybe no one thought about it before, maybe the community did not like the approach… If someone knows, please leave a comment.

You could argue that adding the attribute to every variable that requires some cleanup does not look beautiful, and it is laborious. Yet, I still believe it should be used way more often in C projects that already use compiler extensions. And as we will see in a bit, there are some ways to save a few strokes, especially in the long run.

In case you are wondering why I talked about the cleanup attribute, but then I used __cleanup__ instead: the underscores are optional, and they can save you from collisions in case an existing macro is called cleanup. You can read more about attribute syntax in the official documentation.

The next section is my attempt to help you understand how this attribute is used in the Linux kernel to automatically release memory, and what happens under the hood. Why would you want to know what happens under the hood? Because if you don’t really know what you are doing, you will probably introduce bugs, and you will never be able to extend the mechanism to other use cases. As you will see in a bit, you can easily mess up, and new use cases for this mechanism will arise every now and then. Bear in mind that this feature is rather new in the kernel, and new macros are under review to extend its usage. Bleeding-edge development with 20-year-old compiler attributes!

2. Walkthrough: the __free() macro step by step

The cleanup attribute is really cool, and we are about to see an example where we will use it to free dynamically allocated memory. But typing the whole __attribute ((__cleanup__(cleanup_function))) is too tedious.

Instead, we could define a much shorter macro to call the cleanup function. I know that macros look like black magic for beginners, but don’t worry: they are usually nothing more than syntactic sugar for more complex code.

For example, we could save some typing with a macro like the following __free():

//wherever __free() is used, replace it with this long expression

#define __free(func) __attribute ((__cleanup__(func)))

Let’s use our new macro to automatically free memory when a variable goes out of scope:

/* free1.c */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define __free(func) __attribute ((__cleanup__(func)))

void cleanup_function(int **foo)

{

printf("Avoiding a memory leak ;)\n");

free(*foo);

}

int main()

{

int *foo __free(cleanup_function) = malloc(10*sizeof(*foo));

// Some (probably buggy ;)) code

return 0;

}

I said before that clang also supports the cleanup attribute, didn’t I? Let’s see:

clang -o free1 free1.c

./free1

Avoiding a memory leak ;)

Awesome! Are we done? Well, we still have to pass the cleanup function to our macro. Letting everyone use their own cleanup function for a given type does not make much sense, let alone in a huge project like the Linux kernel. Furthermore, no one wants to memorize the name of the cleanup function for every type. Offering a simple API that hides the cleanup mechanism would be more efficient. The API user could simply call __free(type), and the rest would be transparent. Let’s add a new macro to generate the cleanup functions according to the type:

#define DEFINE_FREE(_name, _type, _free) \

static inline void __free_##_name(void *p) {_type _T = *(_type *)p; _free; }

Wow, wow! What was that? Is that really new syntactic sugar? Yes, it is. Every time you use the DEFINE_FREE() macro, you have to pass a name to generate the cleanup function, the variable type, and the free mechanism. The name could be anything, but the variable type sounds reasonable, so we end up with a cleanup function called __free_type() like __free_int() or __free_foo(). We have used the handy ## preprocessing operator for that. The type is obviously the variable type we want to free, and the free mechanism is the code we want to execute in the cleanup function.

Some beginners might have found a different kind of black magic in the macro we just defined: void pointers. But again, don’t worry. They are useful and actually not that complex. We will use a void pointer to pass any pointer (e.g. a pointer to the variable type), and avoid cumbersome double pointers like the int **foo we used in the last example. Give it a try with void *foo instead, and everything should work like before.

Now that we have our DEFINE_FREE() macro, we can adapt our previous __free() macro to get the generated cleanup function instead:

#define __free(_name) __attribute ((__cleanup__(__free_##_name)))

And now, another example, this time with cleanup functions for int * and a slightly more complex type strcut foo *:

/* free2.c */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

//Some more complex type

struct foo {

char *name;

};

static inline void foo_cleaner(struct foo *foo)

{

printf("Bye %s\n", foo->name);

free(foo->name);

free(foo);

}

/************** OUR "API" internals **************/

#define DEFINE_FREE(_name, _type, _free) \

static inline void __free_##_name(void *p) {_type _T = *(_type *)p; _free; }

//Our cleaner for int *

DEFINE_FREE(int, int *, printf("Bye dynamic int = %d\n", *_T); free(_T))

//Our cleaner for struct foo *

DEFINE_FREE(foo, struct foo *, if(_T) foo_cleaner(_T))

/*************************************************/

/******************* OUR "API" *******************/

#define __free(_name) __attribute ((__cleanup__(__free_##_name)))

/*************************************************/

int main()

{

int *pint __free(int) = malloc(sizeof(*pint));

struct foo *pfoo __free(foo) = malloc(sizeof(*pfoo));

*pint = 42;

pfoo->name = strdup("Javier Carrasco");

// Some code

return 0;

}

This time we have programmed the cleanup in two different ways: directly in the DEFINE_FREE() macro for int * types (a simple free), and as a separate function for struct foo *, because a bit more code was needed. Alright, let’s see if it works:

clang -o free2 free2.c

./free2

Bye Javier Carrasco

Bye dynamic int = 42

Note that the order in which the cleanup functions are executed is not random. In fact, they are executed in the reverse order in which the variables with the cleanup attribute are declared in the scope. This is not relevant here, but it’s something to keep in mind.

If you understood everything I told you in this section, congratulations: the macros I used were taken from the Linux kernel*, and you don’t have to learn the same thing twice. If you are still trying to understand how attributes and macros work, don’t panic: a second, more thorough read will definitely help. Just don’t give up!

* The __free() macro from the kernel is not exactly like mine. Instead, an intermediate step is used to get the compiler-specific syntax for the cleanup attribute, increasing flexibility. What you will actually find in the kernel is

#define __free(_name) __cleanup(__free_##_name), where __cleanup(__free_##_name) is defined as follows for Clang (in compiler-clang.h):

#define __cleanup(func) __maybe_unused __attribute__((__cleanup__(func)))

3. Return valid memory, but keep on using auto cleanup!

What if the allocated memory is required later in the code? Will the cleanup attribute free memory anyway? Of course, it will, as soon as the variable goes out of scope. Does that mean that we can’t use that attribute in that case? No, someone has thought about it already.

We can use the cleanup feature like we did until now to automatically free memory in the error paths, and use a specific macro to return the pointer instead of freeing it. Yet another macro? Yes, and we will see a few more in the next chapter. Get used to them and stop complaining, because they are here to stay, and actually they are really useful.

We have two simple macros at our disposal: no_free_ptr() and return_ptr(). The first one uses a second pointer to store the memory address, setting the original pointer to NULL*. Why? Because the cleanup is going to step in anyway at the end of the variable’s scope. We are not inhibiting the cleanup, at least not explicitly, but the original variable (pointer) will be NULL and nothing will be done. The second variable (pointer) does not use the cleanup attribute, and the memory will not be freed. The return_ptr() macro is just a convenient return no_free_ptr(p).

If you have a function that returns a pointer to some memory, but only if nothing goes wrong, a simple return_ptr(your_pointer) at the end will be enough, and the error paths where the memory should be freed will be covered by the __free() like before. Of course, the caller will be then in charge of freeing the memory when it is no longer needed. If you forget the return_ptr() macro, you will be returning freed memory, which is definitely bad.

no_free_ptr() can be used on its own, and you will find several examples in the kernel. For example this patch uses that macro because memdup_user() frees memory itself if something goes wrong and returns a PTR_ERR() (error pointer). In that case, you don’t want to free the error pointer (big mistake), but propagate the error without giving up automatic deallocation otherwise.

Update: as Harshit Mogalapalli pointed out (thanks for your feedback!), there’s this recent patch by Dan Carpenter that fixes such potential misuse for objects that are directly released with kfree or kvfree by checking too if the pointer is an error pointer (if (!IS_ERR_OR_NULL(_T) instead of if(_T)). As you can see, this area is under heavy development!

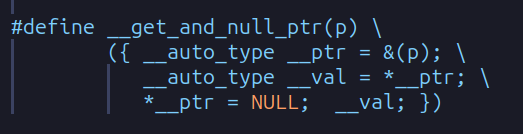

* Technically, no_free_ptr() uses a second macro for it, called __get_and_null_ptr(). This is where the real black magic happens by means of two GCC extensions: ({}) and __auto_type. The first extension is used to define an expression that “returns” a value (__val), and the second one, more obvious, increases flexibility to work with different pointers. This second macro is only used internally, and as I mentioned, it just moves the content of the pointer with automatic cleanup to a new variable. You will find __get_and_null_ptr() in include/linux/cleanup.h as well.

4. Initialize your variables, and fear any “goto”

Some mistake I have seen several times when beginners use this feature for the first time is variable declaration without initialization (think of RAII in other programming languages like C++). What does that mean? Look at the following snippet:

{

struct foo *pfoo __free(foo);

goto fail;

pfoo = malloc(sizeof(*pfoo));

fail:

return -1;

}

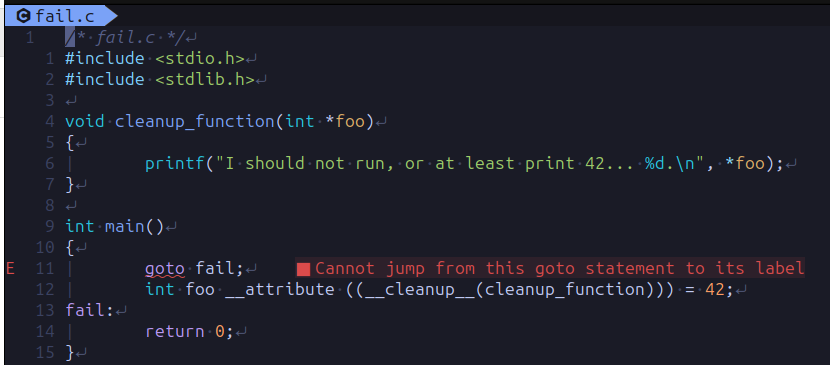

That goto fail is jumping over the variable initialization! When the end of the scope is reached, some random address will be freed! We should have initialized the variable when we declared it. If there was no value for the initialization, we should initialize it to NULL. A more subtle case is the following:

/* fail.c */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void cleanup_function(int *foo)

{

printf("I should not run, or at least print 42... %d.\n", *foo);

}

int main()

{

goto fail;

int foo __attribute ((__cleanup__(cleanup_function))) = 42;

fail:

return 0;

}

Apparently, we have initialized the variable. But it should not matter, because the execution will jump over it, right? Unfortunately, this is not how things work. Let’s compile and run:

gcc -o fail fail.c

(ins) $ ./fail

I should not run, or at least print 42... 0.

# NEVER assume that uninitialized variables are set to 0!

Shit! What happened? The goto does not change the scope/reach of the variable (the block where it is declared), but the initialization does take place where we initialize them. Therefore, declaring a variable that uses the cleanup attribute will basically force us to refactor any previous goto in the same scope, and no new goto instructions should be added before the variable declaration. Thus, declaring them at the beginning of the scope and setting them to NULL when the desired initialization is not possible (because the value is still not available at that point) could avoid such problems.

By the way, that issue was obvious to me because clangd complained about it:

The error message is a bit cryptic, but if we compile the same program with clang, we will get more feedback:

clang -o fail fail.c

fail.c:12:2: error: cannot jump from this goto statement to its label

goto fail;

^

fail.c:13:6: note: jump bypasses initialization of variable with __attribute__((cleanup))

int foo __attribute ((__cleanup__(cleanup_function))) = 42;

^

1 error generated.

Am I suggesting that clang (16.0.6) is better than gcc (13.2.0)? In this particular case… yes, by far! ![]()

This would have not happened if we had used a return instead of a goto. Why? Because the compiler would have reached the return without finding the variable declaration, and it would have not been included in that branch. Moral: if you are using a goto to reach a label that only returns a value, simply return the value.

Jumping around is fun when you are a kid, but good programmers try to hold back. Use goto when you really need it, but be careful, or you will twist your ankle!

5. Why Rust then?

If we can use those macros to automate cleanups, we are making C completely safe! Let’s remove Rust from the kernel and keep on improving our beloved C. Well, there are still many other scenarios where nasty bugs can be (very) easily programmed in C. Ask your favorite chat AI: you will get a huge list of possible mistakes.

Furthermore, the cleanup attribute and the macros based on it can also be misused, and I will give you a couple of real examples… first of all, I believe that refactoring stable code is not always a good idea, even to increase code safety “for future modifications”. We have had a case in the LFX Mentorship where a mentee refactored some code to add the __free() macro without adding the required return_ptr(), and that mistake kept the kernel from booting. The patch had to be reverted, and several people had to get involved to solve the issue as soon as possible. This is how bad refactoring existing code can go. No one notices until it’s too late and shit hits the fan. Don’t you believe me? Then take a look at this recent fix for a regression while refactoring some code in the IIO subsystem to include the cleanup feature. This time, an experienced kernel developer (way, way more experienced than me) introduced the bug, and apparently, this regression could even cause skin burns! ![]() Moral of the story: be cautious because anyone can mess up, test your patch as much as you can, and favor new code or real bugs to introduce this feature until you master it.

Moral of the story: be cautious because anyone can mess up, test your patch as much as you can, and favor new code or real bugs to introduce this feature until you master it.

On the other hand, I am sure that there are still many bugs hidden in the code that could be avoided with this feature. Actually, I fixed myself this memory leak in a driver from the cpufreq subsystem by adding a simple __free()*. It will take a while until everyone gets used to it, but all things considered, I would say that introducing the cleanup attribute was a good idea.

Anyway, competition is always good (like having GCC and Clang competing to become your preferred C compiler), Rust has been a reality in many successful projects for years, and (at least in theory) it could make kernel development more appealing for new generations. So let’s keep on increasing safety for C while letting Rust find its own way into the kernel.

* If you find a similar bug, consider splitting the fix into two patches: one with the “traditional” fix (e.g. adding the missing kfree()), and a second one with the cleanup attribute. This feature is not available in many stable kernels, and the first patch will be easier to backport.

6. Why 1/2?

This article is getting a bit long, and there are still many macros and use cases I did not mention: classes (yes, classes in C!), scoped loops, usage with mutexes… Some of that stuff is so new in the kernel that there is still not much real code to use as an example, but fortunately enough to learn the key concepts and stay up-to-date when it comes to Linux kernel development.

That’s all for today. Please send me a message if you find any inaccuracy, and I will fix it as soon as possible. Stay tuned and don’t miss the next chapter, whenever I get it finished…

Enjoy and share knowledge!